In Virtual Reality News

TL;DR – Starburst is very bulky, VERY bright, gets hot so quite heavy due to all the heat dissipation hardware, but an extremely impressive HDR VR demo.

This week at SIGGRAPH, a leading computer graphics conference, I was able to get hands-on with Meta’s ‘Starburst’ prototype device – one of four recently announced prototype virtual reality (VR) headsets from the company’s Reality Labs research and development arm.

In June, Meta showed off four unique prototype devices, each geared towards solving a particular critical issue in existing VR technology that the company feels need addressing in order for devices to pass what it refers to as the “visual Turing test” – a phrase coined by the Display Systems Research (DSR) team at Reality Labs.

What are Meta’s prototype VR devices?

To recap, the key areas of R&D that Meta is focusing on, along with their respective proposed prototypes and solutions included:

- Varifocal – Requires technology that provides correct depth of focus (versus a single fixed focus), thereby enabling clearer and more comfortable vision within arm’s length for extended periods of time. The prototype designed to start addressing this varifocal challenge being ‘Half Dome 3’.

- Resolution – Meta is aiming for a resolution that approaches and ultimately exceeds 20/20 human vision. 60 pixels per degree (ppd) is generally considered to be “retinal resolution”. The company’s Butterscotch prototype device is able to provide 55 ppd, which is about two and a half times that of Quest 2, which delivers about 20ppd.

- Optical Distortion – This issue requires correction to help address optical aberrations (essentially defects in a lens), like color fringes around objects and image warping, that can be introduced by viewing optics. To begin addressing this issue, Meta repurposed 3D TV technology to create a VR lens distortion simulator. So, no prototype hardware device for this issue, but still just as important to solve.

- Size – For VR to be comfortable for extended periods of time, devices have to be as light and as compact as possible. Meta’s Holocake 2 device is geared towards addressing this issue, and combines holographic and pancake optics. Holocake 2 is the thinnest and lightest VR headset the company has ever built.

- High Dynamic Range (HDR) – HDR technology refers to support of wide ranges of brightness, contrast, and color. Meta’s Starburst prototype has been designed purely with HDR in mind and is aimed at recreating the vividness and brightness that consumers have gotten used to from their TV screens.

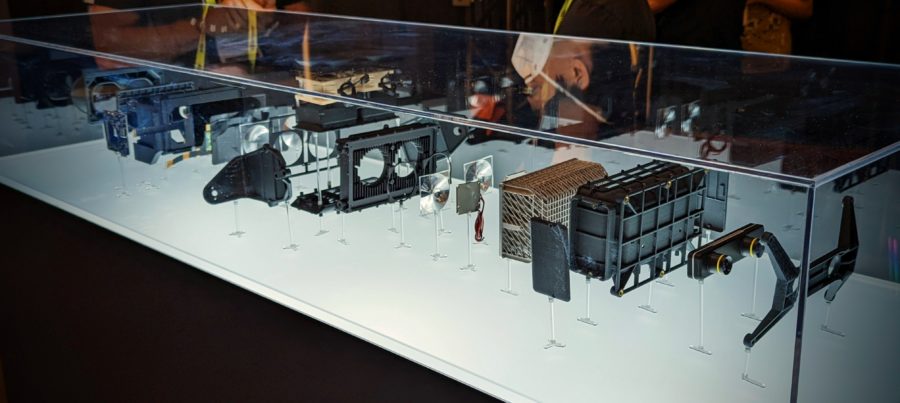

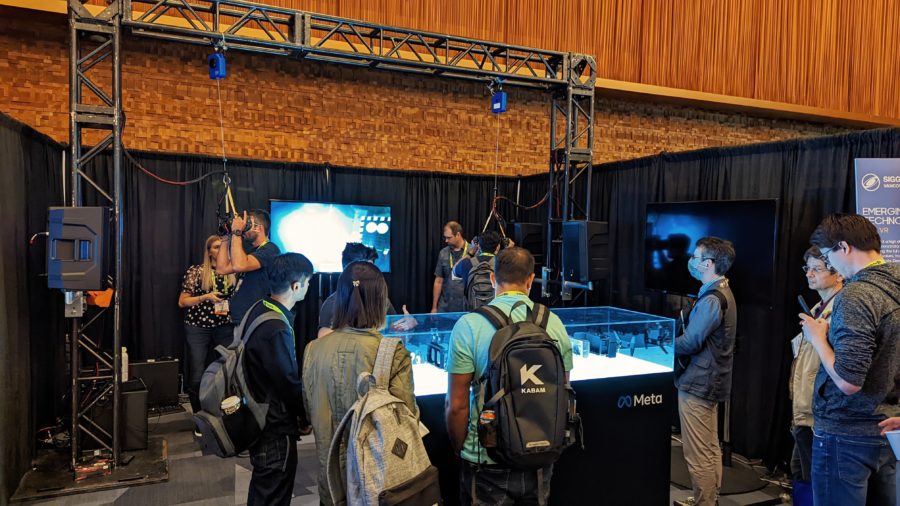

Speaking on site with DSR Research Scientist Nathan Matsuda at SIGGRAPH this week, I was able to learn a lot about Starburst. Firstly, the most noticeable thing about the prototype is its size. Meta’s Reality Labs team had basically rigged up an overhead frame structure that two Starburst devices were suspended from for attendees to try out. The reasons for this were primarily:

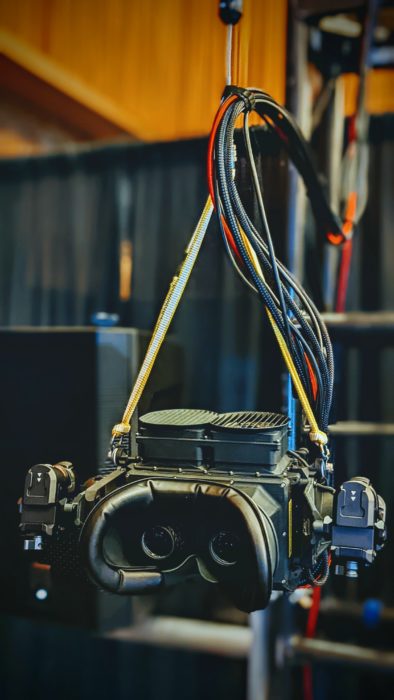

- The device is very heavy for a headworn device. Starburst weighs just over 5lbs (about 2.5 kg). In fact, it was so heavy that you had to hold it up to your face rather than strapping it on your head.

- The device is tethered as it requires a large amount of power for its incredibly bright display.

As the device was extremely bulky, it was also likely suspended more as a precautionary measure, to ensure attendees didn’t actually drop thousands of dollars worth of R&D work.

As noted above, Starburst is designed to help Meta start to address challenges around creating HDR VR. The device’s brightness is measured in “nits” – units that describe how much light an object emits. Typical values for an indoor environment range well past 10,000 nits. Starburst is able to reach a peak brightness of 20,000 nits! For reference, Quest 2 has a peak brightness of about 100 nits, according to Meta.

Why is Starburst so big?

It is Starburst’s peak brightness of 20,000 nits that answers the question of “why is Starburst so big?” The main reason for the device’s size of course, is the fact that something that bright gets very hot. In order to dissipate that heat, Starburst employs the use of rather large 3D printed aluminium heat sinks, which according to Matsuda, account for at least 50 percent of the device’s weight. Then, there are the large fans on top of the device that suck the heat in these sinks up and away from the headset (and ultimately away from the user’s head).

Matsuda also noted that originally when the DSR team first started designing Starburst, there was a hope that it would have to be water-cooled (simply because that would have been… cool). But, as it turns out, water-cooling was not required, and simple fans sufficed and achieved the same outcome. This was mainly due to the fact that water cooling would not have really had any impact on the weight, given that the aluminium heat sinks would still have been required regardless.

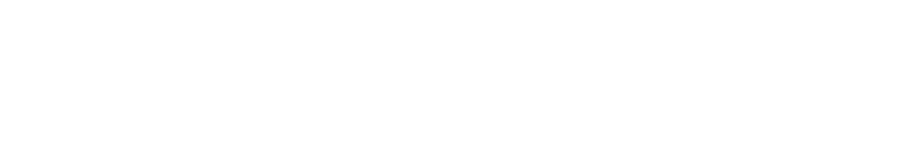

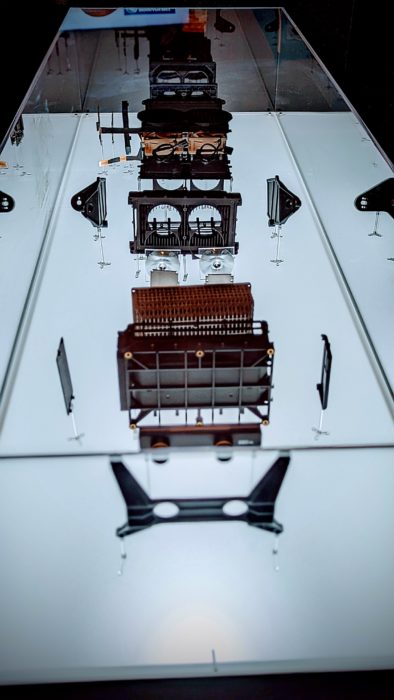

As well as the two hanging and functional prototypes, an exploded view of Starburst was also proudly being displayed inside a glass box. According to Matsuda, the device consists of 36 parts (plus screws).

Resolution is not the goal with Starburst

For resolution, the device is 2560 x 1620px, which works out at about 20 pixels per degree (ppd), so a little less than the Quest 2. The lower resolution was obviously noticeable, but as Starburst is a prototype for demonstrating a solution to an entirely different issue—that of HDR—resolution was really not a huge concern. Besides, that is what Butterscotch is for anyway.

Starburst utilizes both a colour and a monochrome LCD. The reason for this being (according to Matsuda), one LCD on its own provides worse contrast for lower light. If you were to use two colour LCDs, the colour filters would absorb most of the light, meaning there wouldn’t be as much light coming through to the display, which would also mean further battling against thermal restrictions in order to compensate. So, by using a colour LCD in tandem with a monochrome LCD (which has an order of magnitude higher transmission of light compared to colour LCDs), it results in good levels of brightness whilst still having a colour display, so the best of both worlds.

Other areas in which the Starburst prototype currently has to compromise include refresh rate and field of view. However, again as a prototype, this is due to the fact that in order to focus specifically on the aspect of HDR that Meta is aiming to study, things like image quality have to be relaxed.

What was the Starburst demo like?

Still, these compromises really did not detract from just how impressive Starburst was at demonstrating what was an incredible level of HDR and brightness. I wasn’t really sure what to expect before trying out the device, but needless to say I was nothing short of stunned by just how bright the headset is able to go.

The first part of the Starburst VR experience consisted of showing users the same simulation that Meta teased in its Starburst demo reel, with a light source on either side of a virtual space and with some spheres in front to show the reflection of the light. The demo starts out at 100 nits – the same as the Quest 2 device. Everything seemed pretty normal and fine, just like a standard VR experience really, with nothing standing out in particular. Then it ramps up to 1,000 nits, and already the brightness output was noticeably better. Obviously, the urge to look directly at the lights was impossible to resist, and in doing so, it felt almost uncomfortable to stare at them for too long.

Next, the demo switched to an ocean sunset landscape, with the sun creeping through the clouds and reflecting off of the waves in order to showcase the 10,000 nits range. Finally, the experience ramped things up to 20,000 nits, showcasing Starburst’s maximum output. At 20,000 nits, ignoring all the warnings I once received as a child, I stared directly into the virtual sun, and for a moment it genuinely felt like I was looking at the real thing (although definitely not possible, as the sun at noon is about 1.6 billion nits, and this would have almost definitely melted my face off). Finally, the demo threw in some bioluminescence as the sun set, and as the waves started to glow in the short virtual demo reel, it really highlighted the impressive range of contrast that the Starburst prototype device is capable of.

Staring directly at the 20,000 nits light source in the simulation was probably similar to staring directly at something like a 60 watt lightbulb in your house. Except, well, the light source in VR is mere inches from your eyes, rather than suspended from the ceiling and several feet away. Essentially, you knew that what you were looking at was extremely bright and you didn’t want to look at it for too long. Obviously, the intent is not to make a VR device that blinds users, but instead to prove that you can put this level of HDR brightness into VR, which will only result in far more realistic and immersive experiences for users.

Clearly, the power, thermal, and form-factor constraints of VR headsets are huge hurdles that are holding the technology back when it comes to HDR at the moment. It will therefore be a long while before we have untethered VR headsets capable of 20,000 nits output that users can wear all day. But the fact that Meta has started down this road to explore what is possible with HDR VR is certainly encouraging for anyone working to further virtual reality technology.

For more information on Meta Reality Labs’ latest VR prototype devices, you can read the company’s full blog post here.

Image credit: Auganix

About the author

Sam is the Founder and Managing Editor of Auganix. With a background in research and report writing, he has been covering XR industry news for the past seven years.